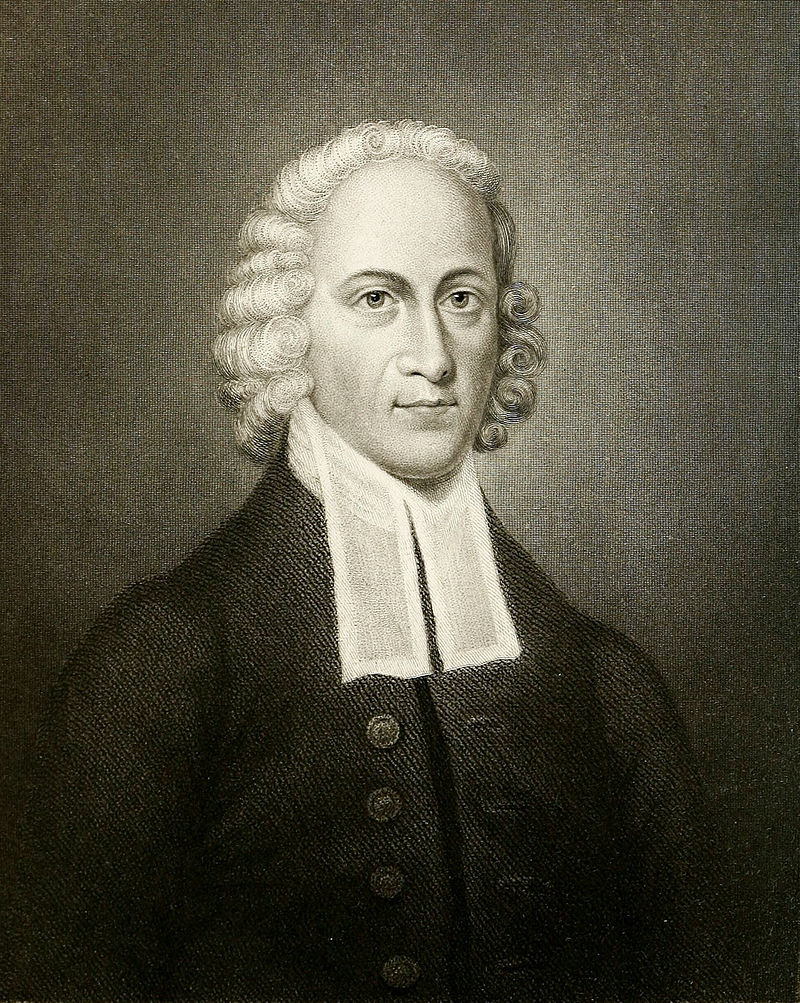

Four Enduring Lessons from Jonathan Edwards’ Lesser-Known Ministry among the Stockbridge Indians

By Thomas Knoff, Ph.D. Candidate | June 8, 2025

Jonathan Edwards, widely regarded as one of Christendom’s great theologians, is best known for his role in the Great Awakening and his formidable theological writings. Less often remembered is his seven-year tenure on the frontier of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he served as a pastor to a small English congregation and missionary to the Mahican Indians. Far from being a period of retreat or “forced exile,” these years proved to be a vital season of ministry and theological output. His move to Stockbridge followed the conflict that led to his dismissal from Northampton. Some believe he accepted the position reluctantly, having few other viable options, while others contend he embraced it as a providential calling. Regardless of his initial reasons for accepting the ministry opportunity, Edwards would later confirm that he regarded this time as a providential opportunity to advance Christ’s kingdom. Though not everyone agrees with all aspects of his theology, few would deny that Edwards’s influence on the contours of Christian thought is both profound and lasting. This article will explore four enduring lessons that can be drawn from this often-overlooked chapter of his life and ministry.

(1) Faithfulness in Obscurity Can Often Leave a Lasting Impact

After being dismissed from his influential pastorate in Northampton in 1750, Edwards could have chosen to retreat into private life or take a more prestigious appointment elsewhere. Instead, he moved his family to the remote village of Stockbridge. Though seemingly obscure, Edwards viewed the ministry as a divinely appointed opportunity. “There are some things remarkable in divine providence,” he wrote, “that afford a prospect of good things to be accomplished here for the Indians” (WJE 16:392).

Edwards’ faithful service in Stockbridge was anything but insignificant. It became a crucible for some of his most important theological writings, including Freedom of the Will, Original Sin, The End for Which God Created the World, and True Virtue. His time among the Native Americans also reinforced his theological vision for the global need for redemption.

LESSON: God often does his most impactful work through faithful obedience in hidden places. Edwards reminds us that obscurity is never wasted when we surrender to divine providence.

(2) Theological Vision Must Shape Missionary Practice

A defining feature of Edwards’ ministry at Stockbridge was the melding of theological conviction with practical mission. In other words, right thinking about God leads to right ministry to others. For Edwards, evangelism was not merely a task, it was participation in God’s redemptive plan for history. He believed revival among the Indians was a “glimmer anticipating the dawn of the millennium,” a sign that God’s kingdom was advancing (Marsden, A Life, 375).

This vision shaped his missional methods. Edwards preached plainly to the Indians through interpreters, tailored his sermons to their cultural and linguistic context, and labored to educate their children. His love for the Mahicans went beyond preaching – he defended them from exploitation, advocated for their rights, and mourned their sufferings. For Edwards, true virtue—love for God and love for what God loves—meant concrete action on behalf of others.

LESSON: Efforts to reach people for Christ that lack a foundation in sound theology can drift into mere sentimentality. Edwards reminds us that true compassion for the lost must be anchored in a deep, God-centered theology that exalts God's glory while earnestly seeking their salvation.

(3) Cultural Sensitivity Enhances Gospel Effectiveness

Though raised in a colonial context, Edwards showed an unusual attentiveness to the spiritual and cultural sensibilities of the Indians. Unlike many of his contemporaries who ignored or mistreated Native Americans, Edwards saw spiritual potential. He noted the Indians’ mystical worldview and moral structure as fertile ground for gospel transformation. His missionary approach involved contextualized preaching, honest treatment, and advocacy for justice.

He also recognized generational dynamics. Older Indians were often resistant to change, so he focused on educating and evangelizing the young. By supporting Indian-run schools and participating in their daily lives, Edwards sought to build trust and gospel credibility.

LESSON: Cultural engagement requires more than surface-level awareness. It requires humility, presence, and the willingness to adapt one’s ministry to meet people where they are.

(4) The Grace and Truth Model has Lasting Missional Impact

While in Stockbridge, Edwards continued to write prolifically. His works from this era are now regarded as theological masterpieces. But they were not ivory-tower treatises. They were deeply connected to his context. Original Sin, for example, reflects his observations of human depravity among colonists and Indians. True Virtue expresses his pastoral burden to cultivate love for God above self-interest.

These works, born out of a missionary-pastoral setting, have shaped generations of theologians and missionaries alike. Edwards believed rigorous scholarship was essential to the church’s health and that theological clarity could catalyze global evangelization. At the same time, his ministry was marked by sincere compassion for the people he served, both settlers and native communities, demonstrating that truth must always be carried in the hands of grace.

LESSON: Though not everyone is called to serve in formal pastoral or scholarly roles, Edwards’ example shows the enduring power of a pastoral heart shaped by deep theological reflection. When love for people is joined with serious thinking about the faith, the result is a ministry marked by compassion and conviction. Such an approach brings depth and influence to ministry, as it meets people where they are with grace and truth.

A Model for Redemptive Urgency

Edwards believed he was living in a decisive moment in redemptive history. He interpreted the spiritual stirrings among Native Americans as signs of the nearing millennial age when “every tribe and nation would see the light of God’s righteousness” (Marsden, A Life, 375). Though he lived on the edge of the Protestant world, he carried a global vision of gospel expansion. His Stockbridge ministry demonstrates that faithful labor, theological integrity, cultural compassion, and scholarly depth can (and should) coexist in Christian mission.

Jonathan Edwards’ time in Stockbridge offers a compelling model of integrated ministry. It must challenge us to live with spiritual urgency, serve from a place of sincere love and theological depth, and trust that even the most hidden seasons of life can become unexpected platforms for the glory of God. Just as Edwards ministered with both conviction and compassion, we too are called to bring theological clarity with a tender sensitivity to people and their unique contexts.

Bibliography

Marsden, George M. Jonathan Edwards: A Life. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003

About the Author

Tom Knoff serves as a Teaching Pastor at Inspiration Church in Mesquite, Texas. He is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Theology and Apologetics program at Liberty University. Tom and his wife Kim live in Texas and have four grown children.

Tom Knoff serves as a Teaching Pastor at Inspiration Church in Mesquite, Texas. He is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Theology and Apologetics program at Liberty University. Tom and his wife Kim live in Texas and have four grown children.