Editor’s Note: Due to the controversies that often surround the book of Genesis, the contents expressed in this article concerning the genre of Genesis 1 belong to the author and may not represent those of Bellator Christi, its affiliates, or contributors.

Genesis Background

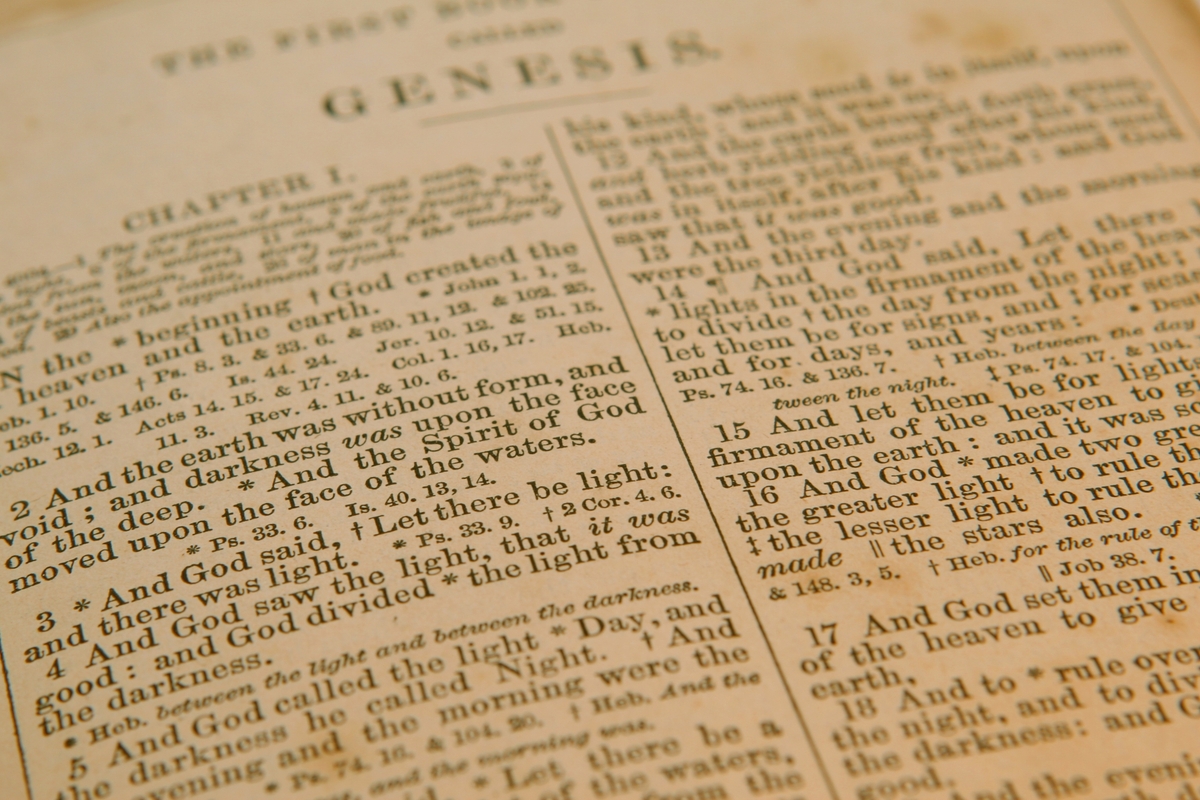

The historical, cultural, and literary distance between us and the writing of Genesis makes it difficult to comprehend.[1] Genesis 1 and 2 have been the subject of never-ending speculation and debate for thousands of years. Who wrote them, and why? What use did the author make of sources? Do they have any value as history? How do they square with contemporary science? My purpose is to take a general look at the creation account laid out in chapters 1 and 2 to identify a few major themes that are communicated.

Authorship: The traditional view holds that Moses is the author. He wrote the book of Genesis sometime during the 40 years in the wilderness wanderings around 1400 BC. However, it is considered anonymous work. Moses is not mentioned as its author, nor is anyone else.

Context: The historical, literary and worldview background setting is the ancient Near East (ANE).[2] Moses was no doubt aware of ANE world views. Kenneth Kitchen, an Egyptologist, has compiled a long and impressive list of details to show that the Pentateuch fits into the milieu of the late second millennium B.C. and its points of contact with the literature of the Near East, in its historical and geographical references, and in its covenant structure.[3] Moses used language and a frame of reference that was known to the soon to be nation of Israel in order for him to relate the true creation account.

Genre: The question of genre is critical to any hermeneutical and exegetical endeavor. Is it historical, narrative, myth, poetry, apocalyptic, wisdom, epistle, or a combination? To be sure, the events of the creation narrative are of such a nature that no record of them can in the strict sense be considered historical, since they antedate man and human writing. Genesis 1:1-2:3 is best characterized as exalted prose narrative.[4] It is a mixture of narrative and poetic elements. John L. Thompson, professor of historical theology,

It is a literary scheme that employs exalted semi-poetic language…both in the content and structure, there are parallels between Genesis 1 and other poetic literature. Repetition of phrases as well as the employment of literary devices such as corollary and silence could put Genesis 1 in the same genre as poetry; however, the movement towards a climax gives it an element of prose.[5]

Genesis Historicity

From Genesis 2:4 forward, it is a historical or prose narrative. Collins notes, “The Hebrew reader has a different feel for the style here: it is more like the normal biblical narrative style found elsewhere in the Bible.”[6] From the opening verse in Genesis and the narrative structure that follows strongly indicates that we are dealing with history.[7] Moses, the author in the ANE context, uses an exalted prose genre to establish three theological objectives: 1. God and who He is. 2. The purposeful creating and ordering of the cosmos. 3. The establishing of humanity and their vocation in relation to God and the created order. To say that theology is the most important aspect of the text is not to say that history is unimportant. The Bible’s consistent witness is that the God of the Bible acts in history. Genesis 1 and 2 testify that he created history.

Genesis describes and embraces supernatural historical events. The opening verse of Genesis states, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” This verse should be viewed as an independent clause summarizing the result of all the individual creative commands that follow it in Genesis 1. It does not describe a separate creative step or a temporal dependent clause. If the various “Let there be” commands are not aspects of an overall event summarized by Genesis 1:1, there exists no reasonable antecedent to which Hebrews 11:3 refers. It is the grand pronouncement of God’s creation of matter, energy, and time. There is nothing comparable in the ANE literature. The triune God is transcendent and eternal in comparison to the contingently created material world. Francis Schaeffer contends, “The universe had a personal beginning–a personal beginning on the high order of the Trinity. That is, before “in the beginning” the personal was already present. Love, thought, and communication existed prior to the creation of the heavens and the earth.”[8] Genesis chapter 1 presents God as sovereign ruler and personal agent who acts by creating. There is an intentional focus on the Creator God that continues in chapters 1 and 2, revealing him in glorious power and majesty. God (אלהים, ’elohîm), as the sole actor on the creational stage, is mentioned over 30 times in 31 verses. He creates, says, sees, separates, names, makes, appoints, blesses, finishes, makes holy, and rests. In fact, God is the subject of virtually every action verb in the wayyiqtol tense here—the chief exception being Genesis 1:12, where the earth brings forth vegetation (although even that is in response to God’s command). New Testament scholar D.A. Carson, from a worldview perspective, adds:

God is separate and different from the universe he creates, and therefore pantheism is ruled out; that the original creation was entirely good, and therefore dualism is ruled out…God is a talking God, and therefore all notions of an impersonal God must be ruled out; that this God has sovereignly made all things, including all people, and therefore conceptions of merely tribal deities must be ruled out.”

In contrast to the exalted monotheism of Genesis 1 and 2, the ANE Mesopotamian accounts present gods as embodiments of natural forces devoid of intrinsic moral principles. They lie, steal, fornicate, and kill. Humans have no special dignity. They are the lowly servants of the gods, being made to provide them with food and offerings.[9] Genesis 1 and 2 identify the existence of a deity unlike those described in ANE cosmologies. God is an omnipotent personal agent, not some phenomenological altering force.

Genesis and False Worldviews

Genesis 1:1 logically implies that worldviews such as atheism, polytheism, and pantheism are false. Genesis makes no attempt to prove the existence of God. Yet Psalm 14:1 states, “The fool has said in his heart, ‘There is no God.'” God’s existence is presupposed and stated as a self-evident truth. Genesis 1 and 2 is an apologetic against rival ancient understandings of creation, such as the Enuma Elish.[10] In Genesis 1 and 2, fundamental truths are declared: creation of all by God, special divine intervention in the origin of the first man and woman, the unity of humans, the pristine goodness of the created world, including humanity. Genesis 1 and 2 demand the recognition of God as creator.

Jerry Bogacz, Ph.D. Cand.: Contributor

Jerry Bogacz was born and raised in the Chicago area. Jerry and his wife Kathy relocated to Lexington, Virginia in 2015 where they reside to this day. As a scientist, Jerry worked as a research scientist and project manager in immunodiagnostic and DNA diagnostic product development for Abbott Laboratories in northern Chicago. Jerry is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Ph.D. in Theology and Apologetics program at Liberty University. He graduated from Biola University with two degrees–an MA in in Apologetics and an MA in Science/Religion. He was a resident in 2013 at the C. S. Lewis Fellowship at the Discovery Institute. Also, Jerry received training at the Cross Examined Apologetics training in 2014. Ministerially, he served as a pastoral and teaching elder at Evanston Bible Fellowship in Evanston, IL (2001-2015). Jerry’s primary areas of research are focused around the integration of science and theology, biblical anthropology, bioethics, and worldview studies.

Notes

I recommend C. John Collins, Genesis 1–4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary as one of the best exegetical treatments of Genesis 1-4. You can search this site for other posts on Genesis; see Is Genesis Historical? Interview with Dr. Todd Wood and Paul Garner (Part 1 and 2)

[1] Genesis comprises the first book of The Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. This word derives from Gk. pentateuchos, “five-volume (book).” Jews call these books the “Torah” (i.e., “instruction”), often rendered in English as “Law” (so Matt. 5:17; Luke 16:17; Acts 7:53; 1 Cor. 9:8). The Jews assign to the Torah a greater authority and sanctity than the rest of Scripture.

[2] The nations/empires that geographically surrounded the land that God promised to Israel from the time of Abraham to around the time of the Divided Kingdom following Solomon’s reign: Egypt, Canaan, and Mesopotamia.

[3] K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), chapters 6, 7, and 9.

[4] C. John Collins, Genesis 1–4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2006), 44.

[5] John L. Thompson, Ed., Genesis 1-11: Old Testament Volume 1 (Reformation Commentary on Scripture) (Downers Grove: IVP, 2014), 13

[6] Collins, 103.

[7] Schaeffer,15.

[8] Francis Schaeffer, Genesis in Space and Time (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1972.), 22.

[9] William LaSor, Old Testament Survey: The Message, Form, and Background of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1996), 21.

[10] The Enuma Elish (also known as The Seven Tablets of Creation) is the Babylonian creation myth whose title is derived from the opening lines of the piece, “When on High”. The myth tells the story of the great god Marduk’s victory over the forces of chaos and his establishment of order at the creation of the world.