By: Scott Reynolds, Ph.D., D.Min. | August 6, 2023

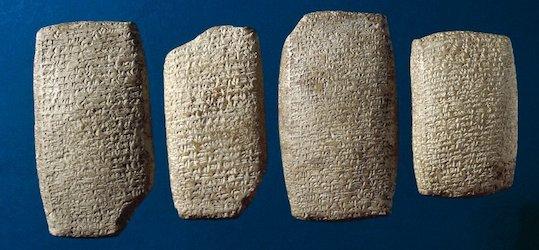

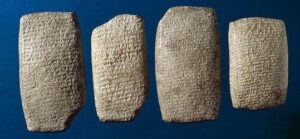

One of the most significant archaeological finds in the Canaanite region is the Amarna letters, a group of several hundred clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”) writing that dates to the fourteenth century BC. The site where the tablets were found is described as: “Tell el-Amarna (the ‘hill of Amarna’), a plain located on the east bank of the Nile River between Cairo or Memphis and Luxor in central Egypt, … where the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1390-1352 BC) and his reformer son Akhenaten (meaning ‘the splendor of Aten’) with his wife Nefertiti made their new capital.”[1]

One of the most significant archaeological finds in the Canaanite region is the Amarna letters, a group of several hundred clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform (“wedge-shaped”) writing that dates to the fourteenth century BC. The site where the tablets were found is described as: “Tell el-Amarna (the ‘hill of Amarna’), a plain located on the east bank of the Nile River between Cairo or Memphis and Luxor in central Egypt, … where the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1390-1352 BC) and his reformer son Akhenaten (meaning ‘the splendor of Aten’) with his wife Nefertiti made their new capital.”[1]

The location of their discovery is significant since Egypt is outside the area where cuneiform writing developed; the Amarna letters testify to the use of the Mesopotamian script and the Akkadian language across the eastern Mediterranean during this period. The majority of the 382 tablets are letters written from rulers of the lands north of Egypt, but a few are letters from the Egyptian king, and there are also tablets inscribed with myths, epics, syllabaries, lexical texts, and other lists—the kinds of texts that were used to learn cuneiform writing.

The Key Apologetic Characteristic of the Amarna Letters

The key apologetic characteristic of these letters is the constant mention of a group called the Apiru, Hapiru, or Habiru. Joseph Holden and Norman Geisler have written, “Scholars have agreed that Apiru (also Hapiru or Habiru) is etymologically equitable to Hebrew. This has led some to believe that the Apiru references in the letters are to the Hebrews under Joshua’s command.”[2]

Alfred Hoerth disagrees with their conclusion and states, “The Hapiru do not seem to fully correspond either in activity, locale, or time with what is known of the Hebrews….The Hapiru were, more or less, a footloose, combative group, and the term Hapiru seems to have become a synonym for one’s enemies.”[3]

However, as Trent Butler observes, the “Habiru were mentioned before the time of Abraham and, therefore, before the birth of the Hebrews as a nation.”[4] The conclusion is that the root etymology of Hebrew does not come from Habiru. Rather, Hebrew comes from Ibri, going back to Abraham’s ancestor Eber; that is, Abraham and his descendants are Eberites (Genesis 10:10-21; 11:10-26).[5]

The Habiru

That does not, however, exclude the possibility that the biblical Hebrews were descended as a specific group labeled Habiru and that with them, Hebrew and Habiru become intertwined because they fit the description of a Habiru, allowing the term to serve as their identification in Canaan until the Hebrews became more established as a people. This is an easy etymological transition, as the Hebrews were slaves in Egypt and were poor and aggressive as they made their way into the lands of Canaan.

Ultimately based on the historicity of the biblical account and the reports found on the Amarna letters, it is highly probable that the Habiru in the letters were the Hebrews.[6] The Amarna letters become some of the most significant artifacts in apologetic archaeology as they deal with the deep conflict of the conquest of Canaan.

The Association of the Amarna Letters with the Date of the Exodus and Conquest of Canaan

One issue significant to the use of the Amarna letters is the probable date of the Exodus and the subsequent conquest of Canaan. The ancient Egyptians themselves kept a record of time according to an astronomical cycle called the Sothic cycle. One of the reasons many scholars today argue for a revised chronology of ancient Egypt is the question of whether the Sothic cycle is a reliable dating method.[7] Comparatively, the Tanakh has a different way of dating the conquest of Canaan.

Jubilee and Sabbatical Years

Historical dating is often difficult, and the people of Israel were not consistently faithful in following the Jubilee and Sabbatical years, as described in Leviticus 25 and 27. However, Levitical priests such as Ezekiel and Jeremiah “were faithful in carrying out their obligation to keep track of the Sabbatical and Jubilee cycles over the years, whether or not the people chose to obey the commands associated with those years. As in other Near Eastern societies, it was the duty of the priests to preserve all calendrical cycles. As long as the priests did this, the system of Sabbatical and Jubilee years was a marvelous device for measuring the years over a long period of time.”[8]

Judges 11:26 and 1 Kings 6:1

Faithful judges and priests followed the cycle allowing Jephthat to know that it was 300 years from the conquest of the trans-Jordan region to his own day. “While Israel lived three hundred years in Heshbon and Aroer and their surrounding villages, and in all the cities that are on the banks of the Arnon, why didn’t you take them back at that time?” (Judges 11:26).

It may also explain how the author of 1 Kgs. 6:1 knew that 479 years has passed from the Exodus to the laying of the foundation of Solomon’s Temple so he could date the latter event in the 480th year of the Exodus era. “Solomon began to build the temple for the Lord in the four hundred eightieth year after the Israelites came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of his reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month” (1Kgs. 6:1). Conservative scholars have traditionally used the the 1 Kings date.

The Seder ‘Olam Rabbah

Later a source older than the Talmud came into use, “the Seder ‘Olam Rabbah, a rabbinic work of the second century A.D., attributed by the Talmud… to Rabbi Yose ben Halaphta, a disciple of the famous Rabbi Akiba. It is widely recognized that Seder ‘Olam Rabbah forms the basis of the chronological reckonings of both the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds.”[9] Seder ‘Olam Rabbah gifted the region a common chronological way to maintain records.

A Defense of an Early Date of the Exodus and Conquest of Canaan from the Amarna Letters

Much of the biblical and chronological cycles work out to the early date of 1406 BC (the early date), while there is some archaeological evidence that points to 1230 BC (the late date) presented later in this chapter. Today, most scholars can agree on dating the conquest to the Late Bronze Age, which includes multiple centuries 1500-1200 and the evidence that speaks to this era. Trying to date the Exodus and the conquest of Canaan to a more specific time remains a theoretical proposition due to the dating methods available at this time.

The problem comes with the conflicting dating of destruction found in the archaeological work throughout Canaan. However, the Amarna letters reference the destruction of Canaan and can be used to piece together the archaeological evidence into a coherent plan. Joshua 8:33–35 The foreigners in this passage would be the Shechemites, and the passage demonstrates a peaceful relationship between the two people groups, a relationship affirmed in the Amarna letters.

The Amarna Letters and the Shechemites

A number of the Amarna letters indicate that the Shechemites were working with the Habiru/ Israelites to expand their territory. Since Lab’avu was a third-generation ruler (EA 253), there was continuity in leadership from the time of the conquest. This could account for a continuing relationship between the Shechemites and the Habiru/Israelites. We have three letters from the king of Shechem (EA 252-254). In one letter, Lab’avu has a somewhat defiant tone that is much different from the letters from the other city-states (EA 252). These letters, coupled with the fact that Shechem was fortified during this period, suggest that Shechem was somewhat independent of Egyptian control and pursuing its own best interests.

- The king of Jerusalem complains that Lab’avu gave the land of Shechem to the Habiru (EA 289).

- The sons of Lab’avu and Miliku, king of Gezer, are accused of giving the land of the king (pharaoh) to the Habiru (EA 287).

- The king of Megiddo charges, “Two sons of Lab’avu have indeed given their money to the Habiru and the Suteans in order to wage war against me” (EA246).

- Lab’avu answers the charge that his son was “consorting with the Habiru” (EA 254).

Conclusion

These references suggest a close alliance between Lab’avu and the Habiru.[10] In addition to the Amarna letters and the Scriptures talking about the relationship between Shechem and Israel, a new artifact has just been made publicly aware that satisfies Joshua 8:30-35 and Deuteronomy 11:29 which states “When the Lord your God brings you into the land you are entering to possess, you are to proclaim the blessing at Mount Gerizim and the curse at Mount Ebal.” Which we will address in the next article in this archaeological series.

About the Author

Dr. Scott Reynolds earned his Ph.D. in Theology and Apologetics from Liberty University and his D.Min from New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. In addition to his doctoral accomplishments, he earned degrees from Troy University. Dr. Reynolds has traveled the world and has served as an archaeologist with some of the biggest names in the field. He brings a passion for biblical studies, biblical history, and an expertise in archaeological studies. Dr. Reynolds is a retired pastor and church planter. He has taught at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and now is now working archaeological digs in a pursuit of discovering the apologetic properties of archaeology. Scott and his wife Lori have two grown children, one granddaughter and a very spoiled dog.

Dr. Scott Reynolds earned his Ph.D. in Theology and Apologetics from Liberty University and his D.Min from New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. In addition to his doctoral accomplishments, he earned degrees from Troy University. Dr. Reynolds has traveled the world and has served as an archaeologist with some of the biggest names in the field. He brings a passion for biblical studies, biblical history, and an expertise in archaeological studies. Dr. Reynolds is a retired pastor and church planter. He has taught at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and now is now working archaeological digs in a pursuit of discovering the apologetic properties of archaeology. Scott and his wife Lori have two grown children, one granddaughter and a very spoiled dog.

Notes

[1] Holden and Geisler, The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible, 239.

[2] Ibid., 240.

[3] Hoerth, Archaeology and the Old Testament, 217.

[4] Trent Butler, ed., Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary (Nashville, TN: Holman Publishing, 2003): 697.

[5] Ibid., 698.

[6] Bryant Wood, “From Ramesses to Shiloh: Archaeological Discoveries Bearing on the Exodus-Judges Period,” Associates For Biblical Research, n.d., (2008): https://biblearchaeology.org/research/conquest-of-canaan/2403-from-ramesses-to-shiloh-archaeological-discoveries-bearing-on-the-exodusjudges-period.

[7] David M. Rohl, Pharaohs and Kings: A Biblical Quest (New York: Crown Publishers, 1995): 390.

[8] Rodger Young, “The Talmud’s Two Jubilees and Their Relevance to the Date of the Exodus,” Westminster Theological Society 68, no. 1 (2006): 71–83.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Bill Shea, “Shechem: Its Archaeological and Contextual Significance,” Associates For Biblical Research, 1993.

Copyright, 2023. Bellator Christi.