Some would suggest that the canon of the Bible is open. That is to say, some think that the canon of the Bible should be reevaluated and open to change. Such advocates indicate that other so-called gospels such as the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Philip should be added to the list of acceptable books. However, it must be asked whether such additions are appropriate. Is the biblical canon open or closed? To answer this question, first the term "canon" will be defined. Then, the process of canonization will be evaluated. Finally, the article will examine the beliefs of the early church as it pertained to the canonization process.

Klein, Blomberg, and Hubbard define the canon as stemming from the “Greek kanon, meaning ‘list,’ ‘rule,’ or ‘standard’” (Klein, Blomberg, and Hubbard, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, 103). The biblical canon refers to “the collection of biblical books that Christians accept as uniquely authoritative” (Klein, Blomberg, and Hubbard, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, 103). The term suggests that the books that comprise what is known as the Bible are the rule of faith being divinely inspired by God. Thus, evangelical Christians recognize the fact, as the Apostle Paul denotes in that “All Scripture is inspired by God and is profitable for teaching, for rebuking, for correcting, for training in righteousness, so that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:16).

Like the Old Testament, the New Testament was canonized by a process. Already by the time the New Testament books were being composed, early apostles recognized them as Scripture to a similar degree to the Hebrew Bible (what we would call the Old Testament). Peter recognizes that individuals were compromising the writings of Paul as, in the words of Peter, “they also do with the rest of the Scriptures” (2 Peter 3:16). Later toward the end of the first century and into the second, leaders like Clement of Alexandria recognized the integrity and inspiration of the New Testament. Clement of Alexandria denotes that,

“We must know, then, that if Paul is young in respect to time—having flourished immediately after the Lord’s ascension—yet his writings depend on the Old Testament, breathing and speaking of them. For faith in Christ and the knowledge of the Gospel are the explanation and fulfillment of the law…that is, unless you believe what is prophesied in the law, and oracularly delivered by the law, you will not understand the Old Testament, which He by His coming expounded” (Clement of Alexandria, Stromata IV.21, 434).

Thus, Clement of Alexandria elevated the writings of the New Testament as a means to understand the Old Testament, as Christ explained the Old Testament in and through His teachings and fulfillment of the Old Testament.

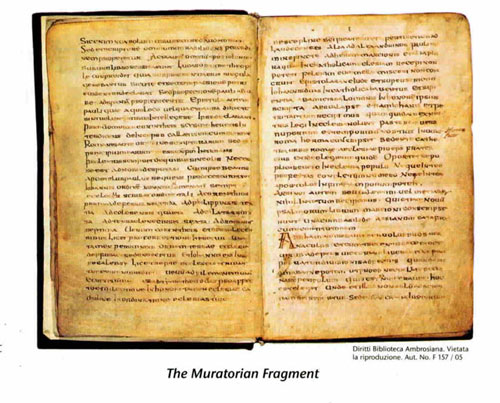

Early canons were comprised, but most notably by the heretic Marcion. Due to Marcion’s limited canon, others such as Irenaeus and more notably Athanasius compiled a complete canon which would be officially accepted at a later time. Irenaeus denotes that a canon was floating about in the early church by stating that Marcion “and his followers have betaken themselves to mutilating the Scriptures, not acknowledging some books at all; and, curtailing the Gospel according to Luke and the Epistles of Paul, they assert that these are alone authentic, which they have themselves thus shortened” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies III.12.12, 434-435). But how did one know if a text was inspired and worthy of canonicity? Norman Geisler denotes five measures of authenticity that was placed upon a text by the asking the following questions: “Was the book written by a prophet of God?...Was the writer confirmed by acts of God?...Does the message tell the truth about God?...Did it come with the power of God?...Was it accepted by the people of God?” (Geisler, “Bible, Canonicity of, Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics, 81-84). Klein, Blomberg, and Hubbard identify the criteria as the text’s “apostolicity, orthodoxy, and catholicity” (Klein, Blomberg, and Hubbard, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, 115). That is, the text had to have apostolic endorsement (if not having been written by an apostle). The text must promote correct doctrine as presented by Jesus and the early church. Finally, the text must be universally accepted by the church.

Which of these elements hold the most importance? In this writer’s opinion, if one were to use Klein, Blomberg, and Hubbard’s list of canonicity, apostolicity would hold the highest importance. If a text stemmed from a true apostle, or friend of an apostle, one would expect the text to be orthodox in its teaching. Many books of antiquity, especially in the second century, claimed apostolic authority. However, only those texts in the first century that were in the time-frame of the earliest church leaders could hold apostolicity. It is difficult to choose which of these criteria are less important, as all of them hold great weight in identifying a text as authentic and inspired.

In conclusion, some hold that the canon should still be open. However, this is greatly problematic for several reasons; however this post will only provide two. First, early church leaders knew of the origins of particular texts. While modern scholarship is excellent in many areas, it is impossible to know with the certainty that earlier church leaders held in knowing a text’s authenticity. In fact, it is in this writer’s opinion that many other texts existed in the first century, most that have been lost to the modern scholar. Thus, modern Christians can speculate, whereas early leaders could know the origin and authority of texts with a much higher level of certainty. Second, the early church preserved the New Testament books for a particular reason. It would be negligent for modern Christians to seek to override nearly 2,000 years of church history in arrogantly claiming that persons today know more about Jesus than those who were physically with Jesus. Therefore, it is in this writer’s opinion that the canon is closed and finalized.

Portions of the preceding article were posted in a discussion board assignment by Pastor Brian Chilton. As in all cases, any documentation should be properly assigned. The use of this information for academic purposes will require documentation as plagiarism will be detected. Portion of the contents of this article have been run through the system SafeAssign.

Copyright. 2015. Brian Chilton.

Bibliography

All Scripture, unless otherwise noted, comes from the Holman Christian Standard Bible. Nashville: Holman Bible Publishers, 2009.

Clement of Alexandria. The Stromata. In Fathers of the Second Century: Hermas, Tatian, Athenagoras, Theophilus, and Clement of Alexandria (Entire), Volume 2, The Ante-Nicene Fathers. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Buffalo: Christian Literature Company, 1885.

Geisler, Norman L. Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1999.

Irenaeus of Lyons. Against Heresies. In The Apostolic Fathers with Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, Volume 1, The Ante-Nicene Fathers. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Buffalo: Christian Literature Company, 1885.

Klein, William W., Craig L. Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, Revised and Updated. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2004.